|

| Kitty Genovese |

As a teacher of criminal law, I have on numerous occasions defaulted to the story of Kitty Genovese to explain the issue of omissions. The story familiar from textbooks goes like this: on the night of Friday March 13th 1964 a young woman called Kitty Genovese was attacked and murdered in the New York suburb of Kew Gardens in the borough of Queens. The attack took place in a densely populated residential area, and though it was established that her cries of desperation were heard by 38 people living nearby, not one of them came to her assistance.

Her death might have been prevented, but the fact that it was not is taken evidence of the anonymity of life in modern cities and the decline in our sense of obligation to come to the aid of strangers. The point in law is to ask questions about the extent of bystander guilt, or whether there should be an offence of 'failure to rescue'.

It should, perhaps, come as no surprise that the 'real' story of Kitty Genovese is nothing like the textbook version. Why, after all, would we let truth get in the way of a good example? But the real surprise is that the story of Kitty Genovese is much more interesting and tells us a great deal more about modern urban life.

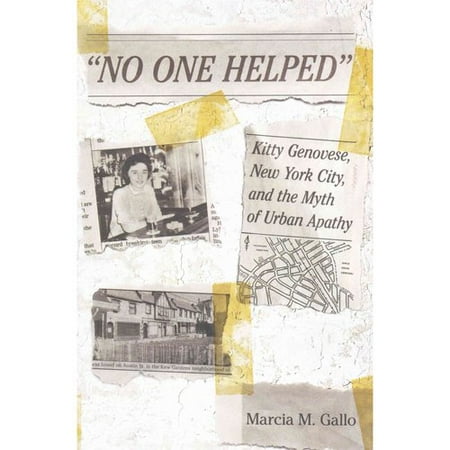

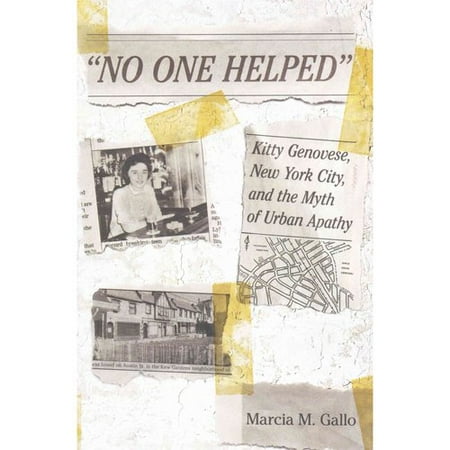

This story is told in a new book called

"No One Helped". Kitty Genovese, New York City and the Myth of Urban Apathy by Marcia Gallo. There are two dimensions to Gallo's story. The first is to uncover Kitty's life, to restore something that was erased by the myth, and to show how it was connected to the story of the development of New York at the time. The second is to trace the origins and development of the legend - how the Kitty Genovese story was created and sustained over the period of over 50 years since her killing.

The first thing that undermines our assumptions is that Gallo shows that the murder was witnessed by at most one person in the neighbourhood, rather than the 38 of myth, and that Kitty was well known to, and mourned by, her neighbours as a lively and friendly woman. Not only was Kitty not an isolated and lonely individual, but she was an independent young woman with many connections in both the city and her neighbourhood. She was a lesbian and lived with another woman in her apartment in Kew Gardens, and enjoyed the growing city precisely because of the opportunities it offered her to be herself - limited as they were at the time.

So why did the myth develop in the way that it did? Here Gallo shows that this was a deliberate strategy employed the new editor at the New York Times to attract readers and try to reconnect with New Yorkers. He sent a special reporter out to interview police and neighbours, and this led to the infamous headline. But what was important here was that it connected with growing fears about crime and the city. The story articulated a new focus on the victim, or at least the idea of victimhood if not the actual victim (and it is interesting to note that the NYT new about her sexuality but did not consider it to be of interest). There was also the fear of apathy and the indifference of bystanders drawing on underlying fears of modern life, and these were ruthlessly exploited by the press, and in a series of books and movies. The real moral of the story is less bystander apathy than media exploitation of a crime story for their own ends.

What is interesting is that a different understanding emerges from Gallo's account, restoring our sense not only of the actual victim and her relationships but also of place and time. This is a valuable and important corrective to the easy assumptions that we often make when confronted with such stories - and it is safe to say that I won't be using the example of Kitty Genovese in this way again.