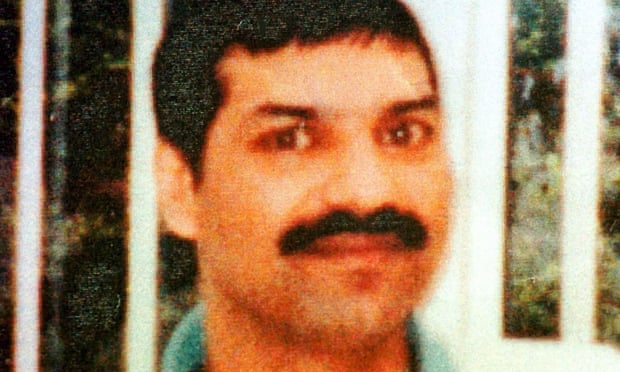

Yesterday saw a momentous event in Scotland - the conviction of Ronnie Coulter for the murder of Surjit Singh Chhokar in 1998. Coulter was originally tried (and acquitted) for the murder in 1999, but was put on trial again this year following the change in the double jeopardy laws in 2011. The four week trial ended yesterday when the jury returned a verdict of guilty for the murder after deliberating for 10 hours.

The story of the case, at least in its early stages, was one of institutional racism and botched decision making. It was fairly clear from the start that three man had been involved in the incident that led to the killing of Chhokar - Ronnie Coulter, his nephew Andrew Coulter and David Montgomery. The Crown then had two separate trials, each of which collapsed when the men on trial blamed the others for the killing. This was heavily criticised by Lord McCluskey at the original trial of Ronnie Coulter. As a result the three men went free.

This was followed by three separate investigations into the failings in the case. The first was an internal investigation by Elish Angiolini (later to be Lord Advocate) into the handling of the case by the fiscal service. The second one, as the profile of the case was rising, was by Sir Anthony Campbell QC into the investigation and prosecution of the offence. And the third, and most damning, was a report by Raj Jandoo into institutional racism in the handling of the case. The Jandoo report found that there was evidence of institutional racism in the failure of the police to consider that the offence might have been racially aggravated, in the failure of the Crown Office to explain its decision making to the family, and in the courts to explain why it was that the trials had collapsed. These issues were to be addressed by the police and fiscal service, but nothing could be done at the time to bring the men to trial again. This changed with the reform of the double jeopardy laws in 2011, which allowed a person who had been acquitted of a crime to be tried again for the same offence, under certain limited circumstances.

The investigation remained open and this year the new prosecution was brought against Ronnie Coulter - with each of the other two men testifying against him. He in turn led a defence of incrimination - that the other men had committed the crime - and that they were blaming him because of a series of family feuds and to avoid their own liability.

The history of the case tracks the developments in Scottish criminal justice over the last 18 years - a period that coincides with the development of devolved Scottish government. One important change, I have already noted, was the reform of the double jeopardy laws, but more important were two larger movements that suggest how Scottish criminal justice was modernising. The first was the increased recognition of human rights, and in this particular context, of the rights of the victim. There have been extensive developments in the law to protect victims as witnesses, to improve the service offered to victims in court, and to render the process of prosecution decision making more open and accountable to victims. The second development is the recognition of hate crime - including forms of racially aggravated crime. These map on to the serious deficiencies identified by the Taylor and Jandoo reports and their have been significant advances in these areas.

This is not to say that there are not still deficiencies - note the recent problems of Police Scotland - or that racist crimes may not still take place. But we can at least hope that victims and their families will receive better and fairer treatment from criminal justice institutions.

Finally, I would like to pay tribute to the family of Surjit Singh Chhokar, and to Aamer Anwar, their solicitor, whosetireless activism has done much to ensure that the case was kept in the public eye, that public bodies were made to account for their actions, and that ultimately the killer of Surjit Singh Chhokar was convicted.

This is a blog about the history, theory and practice of the criminal law. I shall write about books, cases, trials, novels that catch my interest, and even occasionally about current events. My aim is not comment on current caselaw or issues in criminal justice, but to rather to develop a more oblique critique of the law.

Oblique intent

Why the name? Well criminal law afficionados will recognise the phrase 'oblique intent' as referring to a problem of mens rea:can a person who intends to do x (such as setting fire to a building to scare the occupants) also be said to have an intention to kill if one of the occupants dies? This is a problem that has consumed an inordinate amount of time in the appeal courts and in the legal journals, and can be taken to represent a certain kind of approach to legal theory. My approach is intended to be more oblique to this mainstream approach, and thus to raise different kinds of questions and issues. Hence the name.

No comments:

Post a Comment