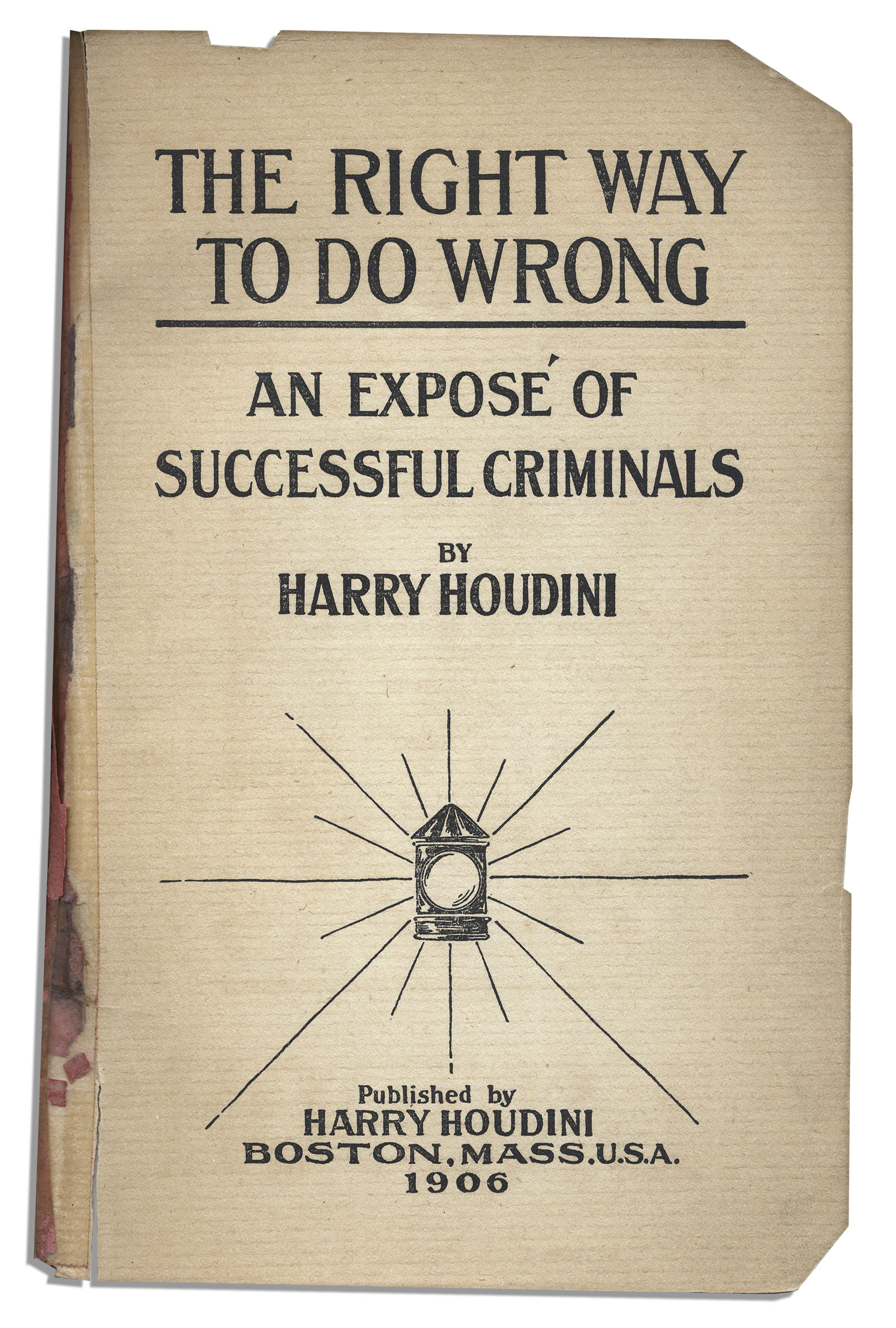

Monday was the 90th anniversary of the death of Harry Houdini, an event apparently marked every year by the holding of a seance - though whether this was Houdini's effort to communicate from beyond the grave or just his final joke at the expense of fake mediums remains unclear. Houdini is obviously celebrated as a famous escapologist, so I was intrigued when I came across a reference to a book that he had written called The Right Way to Do Wrong - promising perhaps a new kind of legal moralism... (thanks to the wonder of the internet you can download it for free here).

Monday was the 90th anniversary of the death of Harry Houdini, an event apparently marked every year by the holding of a seance - though whether this was Houdini's effort to communicate from beyond the grave or just his final joke at the expense of fake mediums remains unclear. Houdini is obviously celebrated as a famous escapologist, so I was intrigued when I came across a reference to a book that he had written called The Right Way to Do Wrong - promising perhaps a new kind of legal moralism... (thanks to the wonder of the internet you can download it for free here).The book is fascinating - even if, sadly, it is less of a guide to legal moralism or to how to be successful criminal, than an account of the various frauds and charlatans that Houdini claims to have encountered over the course of his career. Indeed, he is at pains to make it clear that his aim is not to encourage crime but to allow the ordinary member of the public to safeguard themselves by pointing out the way that thieves and fraudsters work. It is thus an early example of crime prevention literature, advising the householder on the kind of locks to use or the best way to protect their house when they are away, or providing reminders that schemes which promise something for nothing are not always what they seem.

For me, most entertaining was the guide to the types of scams and criminal enterprises operated at the turn of the century. Many are traditional - pickpockets, burglars and fraudsters - that would have been familiar in many cities and countries. But some reflect changing technologies - the railroad or the telegraph and the mail - that opened up new opportunities for the enterprising criminal.

In all of this Houdini presents himself as the honest broker, guiding the naive or innocent around the underworld that surrounds them in this newly urbanised and mobile society where strangers were not always what they seemed. Most of the criminals he exposes had been caught, though a few lucky individuals escaped with their ill-gotten gains. The right way to do wrong, as ever, is perhaps not to be detected.

No comments:

Post a Comment